This is part of Slate’s 2026 Olympics coverage. Read more here.

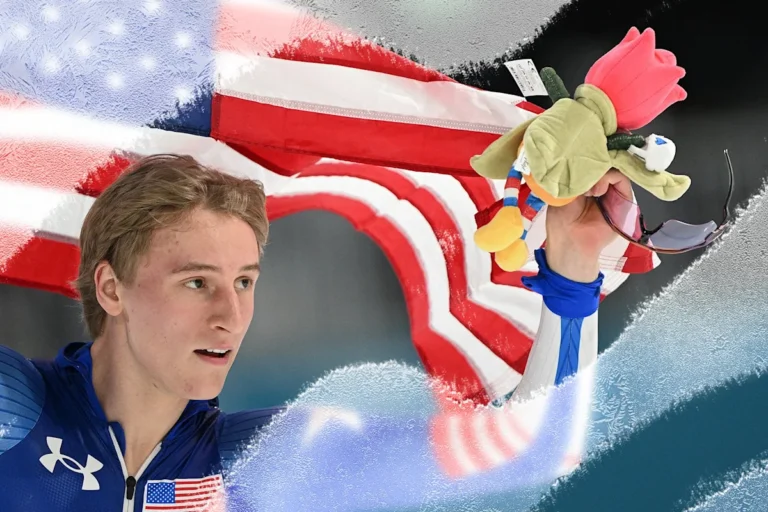

On Wednesday at the Milan Cortina Games, America’s long national speedskating nightmare finally came to an end. With an exhilarating come-from-behind sprint in the last lap of the 1,000-meter race, 21-year-old Wisconsinite Jordan Stolz passed Dutch superstar Jenning de Boo to set a new Olympic record and win gold, to boot. Before Wednesday, Team USA hadn’t won an individual men’s long-track speedskating Olympic medal in 16 years. Stolz’s medal doesn’t just mark the end of a long fallow period in a sport at which America once excelled. It could also herald the beginning of a new golden age.

Advertisement

For decades, American long-track and short-track speedskaters were an international force, with skaters such as Bonnie Blair, Dan Jansen, Shani Davis, and Apolo Anton Ohno racking up Olympic titles. You probably still recognize these names, which speaks to the outsized cachet that speedskating long enjoyed in the United States. Despite the sport’s relative obscurity, America’s top speedskaters have often become crossover celebrities.

Twelve years ago, this stretch of dominance came to an abrupt end. Team USA failed to win a single long-track medal at either the 2014 Sochi Games or the 2018 Pyeongchang Games, and only won a single short-track medal at each. The Americans did a little better in 2022—Erin Jackson won gold in the 500 meters and the men won a bronze in the team sprint—but won no medals at all in short track. Theories varied as to why American speedskating took such a nosedive. Some blamed substandard racing suits. Others blamed U.S. Speedskating leadership. Still others blamed the very mean short-track coach who’d been hired to shape up Team USA.

Maybe the real reason was that Team USA was waiting for Jordan Stolz to come into his prime. As a kid, Stolz idolized Ohno, and emulated him throughout long Wisconsin winters spent skating on his backyard pond. When Stolz outgrew his backyard, his parents took him to one of the closest indoor rinks they could find—the Pettit National Ice Center in Milwaukee, which just so happens to be the best speedskating training center in the United States. There, Stolz worked with a succession of top coaches—including, briefly, Shani Davis—to develop his training routine and skating style.

Stolz’s development skyrocketed when he started working with Bob Corby, a former U.S. speedskater who had coached the 1984 Winter Olympics squad that left Sarajevo empty-handed. The medal shutout gnawed at Corby for years. “I was incredibly frustrated,” he said in a 2024 interview. “I asked myself: what did you do wrong? I thought a lot about it and said to myself: if I ever do this again, [I’d] do it differently.”

Advertisement

More than 30 years later, long after he had forsaken speedskating for a career in physical therapy, Stolz called out of the blue and asked to work with him. (“How can you say no to a 14-year-old kid who calls you on the phone?” Corby remembered.) Corby’s long layoff from the sport gave him a different perspective than many other top skating coaches. While contemporary trends in speedskating development tend to focus on data and analytics, Corby chose to emphasize Stolz’s strength and conditioning. “He likes work,” Corby said. “I pushed him on almost everything, and he just responded.”

This old-school focus made sense for Stolz, who seems to have a preternatural feel for speedskating technique. He excels at timing and turn mechanics, while minimizing “wasted motion” as well as any skater alive. “The things that he does well typically take people an entire career of microadjustments to get there,” 2006 Olympic gold medalist Joey Cheek told NPR in 2023. Gold medalist Dan Jansen concurred: “Jordan’s just a freak. You don’t learn to be as good technically as he is at 18 years old. You have to just feel it.”

Stolz clearly “feels it” while on the ice, which is perhaps one reason why a data-centric training regimen wasn’t for him. Rather than let the analytics tell him how to eke out incremental improvements, Stolz leans into what he already does well, while counting on Corby to push his body hard enough during training so that he can power through the final lap on race day.

This strategy paid off for Stolz on Wednesday. In many of the preceding heats, I watched as skaters took early leads only to run out of gas. Stolz, too, took an early lead against de Boo—but the Dutchman eventually passed him, and led going into the final lap. Then, in the final turn, Stolz made his move, passing de Boo on the inside and surging across the finish line and into the Olympic record book.

Advertisement

Stolz has three races left to skate in Milan Cortina—and after Wednesday’s dominant performance, he’ll be marked as the man to beat in the 500-meter and 1,500-meter events and a contender in the mass start.

If you think the pressure will rattle him, then you don’t know Jordan Stolz. “I like the feeling of being the hunted one,” he told CBC Sports last year. At long last, the rest of the world is chasing an American speedskater—and at these Olympics Stolz might never get caught.

Additional reporting by Rosemary Belson.