We say this every year, but any list of the year’s best music books is even more of a losing proposition than best albums or songs, primarily because of the time investment — so any such list is doomed to being “some of the best music books.” With that inevitable caveat, although this year lacked a jaw-dropping must-read along the lines of Cher’s “The Memoir” or Elton John’s “Me” — which are arguably the most continually satisfying music memoirs of the last decade — there’s still plenty to dig into.

What we music-memoir junkies are usually seeking is, if not the dirt, then at least great anecdotes, especially ones that we haven’t read before. Which brings us to a second caveat: A couple of books in this tally aren’t necessarily compellingly written and would have benefited from a skilled editor, but the stories in them largely deliver the goods. However, that is most certainly not the case with the first on this list…

“The Uncool” Cameron Crowe — For much of the world, he had ’em in his hand with “Jerry Maguire,” or even earlier with his “Fast Times at Ridgemont High” script or “…Say Anything.” But for some of us, Crowe really had us at the hello that was his early career as the world’s most precocious rock journalist. It’s those teenaged salad days that make up the crux of “The Uncool,” his first memoir (and we hope not the last, but if it were, it would be enough). The book really works along two fronts. There are his misadventures as a quiet chronicler of wild talents like Led Zeppelin, David Bowie, Lynyrd Skynyrd and just about every valuable rocker of the 1970s — the golden gods in rock’s possibly most golden age. And then there is his home life, in the California desert and then San Diego, setting the stage with the family dynamics that made him ripe to be turning a keen eye on artists as emotionally intelligent as the Joni MItchells and Kris Kristoffersons of the world. You might think that the stuff at home would not be as enrapturing as the stuff with some of the greatest and most charismatic talents of the 1970s, or that it would be the medicine you have to take to get to the good stuff backstage. But you would only think that, of course, if you’ve never met his mother… which is to say, if you’ve never seen “Almost Famous,” the autofictonal movie that first introduced some of the characters we spend more quality time with in this book. In the glibbest possible way, I’d call this “Almost Famous: The Novelization,” just to get you to read it, as something that takes off from a milieu you’ve already known and loved. But really, “The Uncool” is better than “Almost Famous,” if we were to something as uncool as make comparisons; it might be the best thing he’s ever done.

The memoir goes beyond the movie in introducing us to some unforgettable characters in his nuclear family who got left out of the film — like his dad, a sympathetic soul who would stay up to record concerts off the radio for Crowe, and a second sister, troubled by demons no one can fathom, who introduces him to the joys of rock ‘n roll before taking leave of this world. The psychological connections there boggle the mind, but young Crowe obviously found a way into extreme music appreciation that acted as a healer. It’s with already acute psychological understandings that Crowe enters into his life as a not-quite-fly-on-the-wall witness to the stars. The prose is so cut-to-the quick, and so beautiful, that we better understand why Crowe was destined to become a contemporary to the greats he wrote about and not just to be their scrivener. Whether you want to better understand the eternally intriguing questions of Why Music Matters, or whether you want nothing more than just great anecdotes about Bowie or Gregg Allmann freaking out or Kristofferson or Gram Parsons being super-cool, “The Uncool” takes its place among the great rock books. —Chris Willman

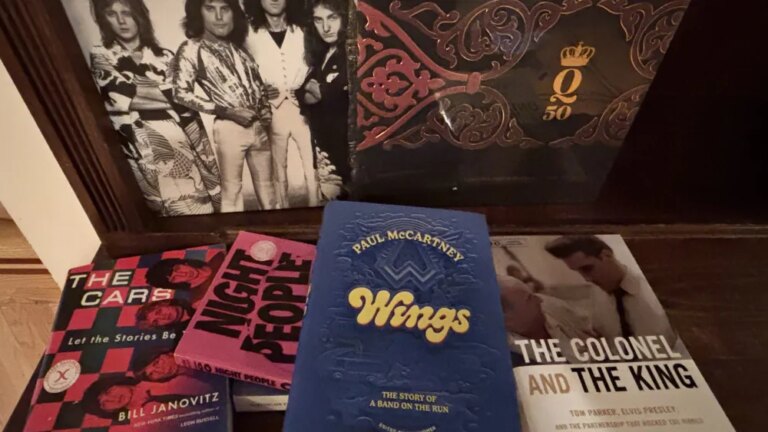

“The Cars: Let the Stories Be Told” Bill Janovitz — For a legendary multiplatinum group with loads of hits — and who were the first “new wave” artist that a lot of Americans heard — the Cars are surprisingly underrated as a band (a situation largely caused by their near-catatonic stage presence). Yet a mighty band they were, with five perfectly interlocking musicians uniting around frontman Ric Ocasek’s idiosyncratic yet indelible songs, which, as evidenced by his tepid solo career, were nowhere near as strong without them. Like Janovitz’s Leon Russell biography, this bricklike tome tells you virtually everything you could possibly want to know and more besides, resulting in an exhaustive history that can verge on exhausting; the fact that Ocasek and the group’s troubled other lead singer, Ben Orr, are both deceased makes for multi-dimensional yet obviously incomplete portraits here.

Yet the chapters on the early years — various bandmembers saw the Beatles, Rolling Stones and Velvet Underground in concert during the 1960s — and peak era shine through the at times too-voluminous details and relitigation of half-century old arguments. At the end of 500+ pages, two overriding impressions emerge: What a fantastic band the Cars were — Janovitz, frontman of Buffalo Tom, has informed and perceptive commentary on the music — and what a charismatic, compartmentalized and mercurial figure Ocasek was (“When he smiled, it was like the sun coming out,” more than one person says). His archival interviews are much less revealing than the comments of the bandmembers and especially his ex-wives, including Paulina Porizkova, who has especially vivid comments. Through it all, a multilayered portrait of a brilliant yet complicated artist emerges, leading to the inevitable conclusion: Stars, they’re not just like us. — Jem Aswad

“The Colonel and the King: Tom Parker, Elvis Presley and the Partnership That Rocked the World” Peter Guralnick — Guralnick already wrote the absolutely definitive two-volume biography of Presley, “Last Train to Memphis” and “Careless Love,” and anyone who has not read those books is advised to stop reading this immediately and turn straight to them — here, Guralnick writes under the assumption that the reader’s familiarity with the King’s history is at the very least deeper than Baz Luhrmann’s entertaining but extremely hagiographic 2022 biopic. Yet even in those far-ranging books, the Colonel remains a mystery, and Guralnick has done a masterful job of uncovering the history of a man — real name: Andreas Cornelis van Kuijk — who was fiercely determined to hide his origin story.

Through conversations with the people closest to the Colonel, culled from both new interviews and Guralnick’s decades of research and conversations — and most of all, Parker’s vast archive of letters, which Guralnick had complete access to — we get a deeply detailed portrait of an ambitious and fast-talking native of the Netherlands who abruptly and inexplicably cut ties with his family. To the degree humanly possible, we follow his early years and first, failed attempt to emigrate to the United States (he quickly tried again and succeeded), his years in the U.S. Army and his early, self-glorified career in traveling circuses — an experience that would shape his entire approach to life. He earned his chops in the music world by successfully managing singer Eddy Arnold and early country-rock singer Hank Snow, but once he met Elvis, the King was all he could see. From that point on, “The Colonel and the King” is basically a counterpoint to his Elvis biography, and Guralnick is sparing with his repetition, often chiming in — in the first person — to summarize already-told tales. Yet vivid new details emerge — at one point, a schoolteacher is at an early Elvis concert and sees a former student losing her mind, as so many did, during her performance.

Asked what all the fuss is about, the former student’s reply summarizes the King’s appeal in 1950s America better than any music critic or cultural historian ever could. “Aw Mizz Axton,” she replies. “He’s just a big ol’ hunk of forbidden fruit.” — Jem Aswad

“Wings” Paul McCartney / “The McCartney Legacy Volume 2: 1974-1980” Allan Kozinn / Adrian Sinclair — If anyone ever felt that that 1970s/ Wings-era Paul McCartney was insufficiently documented, they’re drinking from a firehose this year. While Tom Doyle’s 2013 book “Man on the Run” is a concise and compelling overview that should suit most fans just fine, these two imposing tomes fall under the “everything you could ever want to know and then some” category. Like his first volume (covering 1969-73), Kozinn’s doorstop goes into near-daily detail about McCartney’s recording sessions, tours, business and life. While the attention to detail is formidable in its execution, this era covered the peak of McCartney’s ‘70s popularity although not the peak of his creativity (that was in the previous volume) so these graduate-school-level deep-dive details on albums like the treacly 1978 set “London Town,” or mediocre peripheral efforts like his brother Mike McGear’s solo album, can sometimes strain one’s attention.

More digestible is “Wings,” an oral history of those years told via interviews with dozens of musicians and friends, as well as McCartney himself and his late wife and Wingsmate Linda, who died in 1998. It is no understatement to say that she was unfairly Yoko’ed, and while her skills as a keyboardist were rudimentary, her singing in particular remains an essential component of McCartney’s music at that stage, and her personality emerges vividly in these pages — her commentary is often more engaging and revealing than that of the man himself. — Jem Aswad

“Ozzy Osbourne: Last Rites” Ozzy Osbourne with Chris Ayres — With the bounty of biographical material available on our dear departed madman, this memoir of his final years — which arrived just weeks after his death last July — is definitely not the place to start. But it’s filled with details about those years, ranging from voluminous medical setbacks to some great Keith Moon stories — and no shortage of gratitude. The most touching is probably his re-connecting with Sabbath drummer Bill Ward after a decade of estrangement.

“‘I love you, y’know,’ I told him,” Osbourne wrote. “It went very quiet for a moment on the line. ‘I love you too, Ozzy, you fucking lunatic.’ That’s one of the great things about getting older. Even if you’re a working-class guy from Aston, you stop being as scared of showing your emotions. Because you know that if you wait too long to tell someone how much they mean to you, the chance might never come around again.” As the rare artist lucky enough to perform at his own tribute concert — two and a half weeks before his death, no less — despite his fragile condition, Ozzy’s final weeks were almost as charmed as his life. — Jem Aswad

“Night People: How to Be a DJ in ‘90s New York City” Mark Ronson — In his debut memoir, the Grammy-winning producer-songwriter-DJ doesn’t lean on the studio stories that yielded canonical records from Amy Winehouse and Bruno Mars. Instead, he traces the grooves of New York City’s bygone nightlife through the lens of his scrappy days as an aspiring DJ. Ronson paints a portrait of 1990s club culture as a fantastical playground, where one night you could be spinning for Jay-Z and the Notorious B.I.G. and the next rubbing elbows with Q-Tip at a record exchange. His stories are so conversationally written to the point where a mention of growing up with his friend Sean — Sean Lennon, of course — is so par for the course that it reads as a footnote. All of his tales and stories are threaded through a running list of the music that made him, and how records from Bobby Caldwell and Redman influenced the musician he would inevitably become. For those who remember Ronson’s days as a DJ on the Tommy Hilfiger tour in 1997, “Night People” is a treasure trove; for the rest, it’s a fascinating starting point. — Steven J. Horowitz

“Yoko: A Biography” David Sheff — Sheff has walked this road before: He wrote the famous expansive Playboy interview with Yoko and John Lennon at their Dakota apartment just months before Lennon’s assassination, and even titled his own memoir “Beautiful Boy: A Father’s Journey Through His Son’s Addiction,” after a song from “Double Fantasy.” Yet over the years, he befriended Ono and came to a rare understanding of her life and art: Her family’s Tokyo home being destroyed by U.S. bombers and their ensuing poverty; her work with avant-garde art groups in New York before meeting Lennon; her broken marriage to American film producer Anthony Cox; her custody battle and the subsequent loss of their daughter, Kyoto, for over 25 years. And not least the ongoing nightmare of Ono’s demonization by Beatles fanatics who saw her as the cause of the group’s breakup — even after Lennon admitted to conceling Ono’s credit for co-writing songs such as “Imagine” (which was rectified in 2017) due to his own fragile male ego. While Ono’s stature as an artist has largely been rehabilitated, Sheff brings hue and shading to her story. —A.D. Amorosi

“Hitchcock and Herrmann: The Friendship and Film Scores that Changed Cinema” Steven C. Smith — It can feel like every great artist of the 20th century has already had a definitive biography or two written about them, and most certainly have. Yet there’s fertile ground in the realm of the intersectional biography, books that focus on the chemistry of two souls in tandem and how (to borrow a phrase from Schwartz) they changed each other, and the world, for good. There was a nice example of that this year with “John & Paul,” which aimed to portray the oft-comative relationship of the Beatles’ primary movers and shakers as “a love story.” There’s a similar sort of creative romance food in “Hitchcock and Herrmann,” which explores the greatest ongoing composer/director collaboration in the history of the movies. (We’ll say that with apologies to Williams and Spielberg, knowing they would likely leap to agree.) There is just enough background on both Bernard Herrmann and Alfred Hitchcock that you will feel like you’ve kind of gotten a pretty good biography on either of them… which doesn’t negate the need to go back and revisit Steven Smith’s own 1991 book focusing on just Herrmann.

But when geniuses like these did most of their best work together — in a 10-year run that included “Psycho,” “Vertigo,” “The Man Who Knew Too Much” and “North by Northwest” — it’s especially fruitful to mine the ways in which they not just produced the work but managed to reveal so much about themselves and each other in that work. They had such distinctly different personalities; Hitchcock would avoid walking across a set to evade conflict, whereas the fiery Herrmann would march right into it, like a firewalker. Yet as romantic obsessives with a view of the world that was both tragic and beautiful, they could almost have been twins. And Smith’s easily understandable explanations of the motifs and technique in those classic film scores very much increases our awe for what could happen when two different mediums combine to create pure rapture. —Chris Willman

“Blood Harmony: The Everly Brothers Story” Barry Mazor — Speaking of “intersectional biographies,” nothing quite counts as that as a book about two brothers whose personal and professional lives intersected almost from their first days to their last. Excepting, of course, the 10 years where they simply didn’t speak to each other. Mazor’s Everly Brothers book takes its title from the term used to describe the close harmony that — at least in widespread belief and lore — can only be achieved by singers who share some of the same genetic makeup. But “Blood Harmony” also has some irony built-in, as a title, since there was rarely a wealth of personal harmony betweeen Phil and Don Everly. Meanwhile, if there’s anything you could say about their off-stage relationship, it’s this: There will be blood. (Figuratively.) But even if the personalities of these siblings were so polarized that it would’ve seemed on paper like any career-long intertwining was not to be, God had other ideas. There had been lesser attempts at an Everly Brothers bio, but it’s hard to believe it took till now for a great one to be produced that properly explores their lineage and impact — would there be a Beatles without the Everlys? (likely not) — as well as the chemistry that makes their lives worth charting over a career that lasted a half-century. Better late than never, but best that the task finally fell to veteran roots music chronicler Mazor. There’s a fantastic harmony between him and the written word. —Chris Willman

“Queen & A Night at the Opera: 50 Years” Gillian Gaar — After all the histories, documentaries and hagiography (i.e. the 2018 “Bohemian Rhapsody” biopic), there may not be much left to uncover about this, one of the greatest albums of the rock era. But as this lavishly illustrated coffee-table book shows, there’s always plenty to see: The text is essential, of course, but the real substance here is in the photos, which range from vibrant shots of the band’s early years, the “Opera” era and tour, and familiar ephemera like record artwork, tour passes and the like. If pictures paint the proverbial thousand words, this collection take you back to 1975 in fittingly regal fashion. — Jem Aswad

“Waiting on the Moon” Peter Wolf — The longtime solo artist and former J. Geils frontman is legendary for his incredible, Zelig-like stories from a life in rock and roll, and this book shows why. The book is unconventionally organized: Rather than a chronological history, its chapters are more like a series of cameos with the incredible people he’s known over the years: There are chapters on or featuring Bob Dylan — whose very early Greenwich Village performances Wolf witnessed as a teen — Muddy Waters, John Lennon, the Rolling Stones, Alfred Hitchcock, Tennessee Williams, Lou Reed, David Lynch and more, and nearly all of them treated Wolf as a peer. Despite the trajectory of his life — growing up in the Village, becoming a popular DJ in Boston before joining Geils and, later, marrying Faye Dunaway at the peak of her acting career — it almost doesn’t seem possible that one person could be in such proximity to legends.

As Dylan himself writes in the book’s jacket blurb, “This book reads like a fast train and you’ll get a glimpse of everyone passing by through the windows. Characters that have crossed Pete’s path who he’s known up close and personal. A diverse crowd, one you wouldn’t think belong in the same book: Marilyn Monroe with a scarf on her head sitting next to him in a movie theater, Muddy Waters, Faye Dunaway, David Lynch the filmmaker, Eleanor Roosevelt, Jagger, Tennessee Williams, Merle Haggard.” Yet there’s little question that the most fascinating chapter is the one on Dylan’s early years in the Village — we won’t spoil it, but we’ll just say that the book’s most remarkable quote is when Wolf asks his father incredulously, “‘Dad, you know Bob Dylan?’” — Jem Aswad

“Bread of Angels: A Memoir” Patti Smith — For many people, there’s a hubris to penning one’s autobiography in multiple volumes — after all, how many I’s need to be dotted, let alone in detail? Patti Smith, however, has taken on different themes with each other her memoirs, ranging from her award-winning tome on her early years and relationship with the late Robert Mapplethorpe (“Just Kids”), her soliloquies on deceased friends and family (“M Train”), a treatise on her love of lush greenery and the bucolic texts of Walt Whitman (“Woolgathering”), and her journal of travels, real and imagined (“Year of the Monkey”).

In “Bread of Angels,” Smith moves more broadly across her lifetime’s timeline with rich, ruminative focus on a poor childhood spent in Philadelphia — how there she discovered art (the Modigliani paintings she equates to her own lanky frame) and poetry (first from an elderly neighbor, then stealing a book of Rimbaud poems — a worthy crime in her estimation). Smith talks of connecting later with such important New York figures as Tom Verlaine and Lenny Kaye ,and forging the spikey words and music that became “Horses,” her seminal 1975 debut album. She also reveals several truths about her own background, and the child she gave up for adoption, in tender-but-taut language. Then there is the story of her “lost” years after retiring from public life to raise a family with marry MC5 guitarist Fred “Sonic” Smith. In tackling that topic, she shows off a plain-spoken grace when writing of her desire — her choice, she emphasizes — to shed the skin of rock stardom so to fully give herself to marriage and motherhood. That this same sudden catholic devotion to family spilled over into a more skillful, soulful brand of writing, then, is what gives us the Patti Smith we see now — a woman of letters, more content to pen books than new albums. — A.D. Amorosi

“John Williams: A Composer’s Life” Tim Greiving — Tortured artists make for great biography subjects. But then what is a biographer to do with John Williams, one of the greatest composers of our or anybody’s lifetime, but also one of the most avuncular? Well, plenty, of course, just with the work itself, for starters, which seems to spring from a bottomless well in which there is no limit not only to the talent but the variety of forms in which Williams has had at his effortless-seeming disposal. But there is psychology to be explored there beneath all that journeyman genius, and Greiving knows how to get at it, even if his subject is in most ways the opposite of a tortured or oft-thwarted soul like a Bernard Herrmann. Greiving, one of film music’s top chroniclers, gingerly but firmly explores the effect that the death of Williams’ early wife had on his persona and his output around the time of his first “Jaws”-era prime. Ultimately, though, this was destined to be as feel-good as any book about a composer ever could be, because when you think about someone who is arguably the very best at his craft as anyone who ever lived, and is popular recognized as such through a majority of his lifetime… what could feel better? Not much, except for a night at the Hollywood Bowl with a bottle of wine, listening to a compendium of his music. Short of that, this is the next best thing, as a celebration of the sweet nexus where innate genius meets an intense dedication to hard work and craft, with a shockingly friendly face on top. —Chris Willman

“Giant Steps: My Improbable Journey From Stage Lights to Executive Heights” Derek Shulman with Jon Wiederhorn — A memoir from the former lead singer of prog-rock titans Gentle Giant who went on to become a label executive (signing Bon Jovi and Pantera) may not be on the level of Cher’s autobiography, but what’s actually most interesting here are the stories from Shulman’s life outside the band. The book opens with an unimaginably horrible scene — a 16-year-old Shulman and his entire family watched his musician father die of a heart attack right in front of them — yet its overall tone is warm and positive, as Shulman and his two brothers find success quickly as the pop group Simon Dupree and the Big Sound during the Brit Boom of the mid-1960s. They record with George Martin at the legendary Abbey Road studios while surrounded by the royalty of the era; a highlight of the book comes when John Lennon and Yoko Ono catch them jumping on the bed that the couple had moved into the studio so Ono could recuperate from an auto accident. Other highlights include having a pre-fame Elton John (who contributed a blurb) as their keyboardist on a tour of Scotland, a chaotic 1970 U.S. tour opening for Black Sabbath, and the descriptions of life on the road in “Almost Famous”-era America. Unlike virtually every other musician of the era, Shulman is a teetotaller, so his memory is better than most (the stories are unchanged from when this writer heard them while working for Shulman at a Warner Bros.-affiliated label, more than 30 years ago). — Jem Aswad